Real time BLE sniffing in the shell with nrfutil and tshark

Over the past few months I have launched a foray away from my development mainstays and into Bluetooth. Specifically, reverse engineering a BLE protocol for an IoT device in order to interop it with Home Assistant.

To this end, I have spent a lot of time in the Wireshark GUI in order to capture live BLE packets with my nRF52840 BLE sniffer. As a small part of that overall work, I have a wish to create some simple portable scripts in order to automate the process of extracting a unique key over the air for the device in question.

Unfortunately, the straight-forward approach using tshark with the same capture interface as the Wireshark GUI doesn’t work out of the box with the Wireshark extcap plugin that is installed by the new nrfutil ble-sniffer bootstrap CLI command. No surprise, given tshark is not officially supported. But I won’t let that stop me.

This article documents my deep dive into the challenges around grabbing live BLE packet stream from an nRF Sniffer in such a way you can script over the stream in a shell environment.

My day-to-day development environment and typical target platform is anything Unix-like, but I give Windows (native Windows, i.e. Powershell) equivalent attention in this article due to my use case. Windows has some particular idiosyncrasies that mean solving this problem for some of the simpler use cases is slightly more involved than it is in Unix. Regardless, for both platforms and for different typical use cases, I will provide jumping off points F

At a high level, we cover:

- Disambiguating the new

nrfutil ble-sniffer(that we focus on) from older packages. - The difficulties in using

tsharkdirectly with the capture interface (packet capture stops by itself). - The difficulties trying to use

nrfutil ble-sniffer sniffdirectly to pipe the raw capture byte stream in real time. - A technical exploration and analysis into how and why realtime capture works via the extcap plugin inside the GUI flavour of Wireshark.

- Using that analysis to arrive at a better working solution that enables (with the new sniffer software):

- Live tail of the raw packet data bitstream in Unix and Windows (Powershell) shells.

- Using that with

tsharkor whatever you like.

This post is targetted at folks who need to do the same, and so you likely have some familiarity with the tools, protocols and hardware involved. It may form a multi part series on other aspects of BLE-related tinkering in my pursuit.

Clarification on nRF software packages#

To avoid confusion and to gain important context, I am unfortunately going to have to inundate you with the intricacies of the current nRF software landscape up front.

There are effectively two official parallel software packages to interface with an nRF device capable of BLE sniffing from host machine. This is because Nordic are/have recently rebuilt their tooling ecosystem.

Confusingly, each option appears with the same name at various points in the documentation, yet the versioning scheme for them is completely different and they are built on different technologies. The docs of each package are somewhat muddled and conflated with each other at times, which I’m sure is just a teething issue related to recent changes. At the very least, you have to be careful to check what is being referenced when searching around these tools.

Here’s my attempt at breaking down the key differences.

Old Tooling#

The open source Python-based nRF Sniffer for Bluetooth LE, distributed as:

- A Python “core” module called

SnifferAPIthat contains all the low level hardware interface code. Documented here. - A Python

extcapplugin for Wireshark which amounts to a thin wrapper aroundSnifferAPI. Documented here. - Also comes bundled with the nRF device sniffer firmware binaries which are to be used with flashing software like the nRF Connect Programmer App.

It’s typical end-user interaction patterns are therefore via:

- The Wireshark GUI and associated command line tooling, including

tshark. There is a manual installation process of the extcap plugin by way of copying into Wiresharks plugin directories. - Python programmatic interface for the sniffer functionality.

Other tasks you might expect an end user of my scripts to need to do, like preparing the firmware of their device, are accomplished with other packages.

New Tooling (focus of this article)#

The closed source nRF Sniffer for Bluetooth LE which is distributed as part of the wider unified ecosystem of nRF Util v7+.

Note that this is not to be confused with the previous versions of nRF Util like these long-since deprecated repositories, which are before the rewrite.

This new ecosystem provides a kind of package manager and unified CLI interface over those packages, and such has a much wider scope. Individual packages cover areas such as device flashing, low level serial interfaces, and whatever else that is, or will become, part of the nRF ecosystem.

In order to try to scope this to a more direct comparison, I will focus for a moment specifically on the the nRF Util ble-sniffer package which surfaces as nrfutil ble-sniffer <command> on the CLI tool. This ultimately consists of:

- A Rust-based binary executable

nrf-ble-snifferthat serves as the “core” and contains the low level hardware interface code. - A Rust-based binary executable

nrf-ble-sniffer-shimthat serves as theextcapplugin for Wireshark. This is a thin process-to-process interface that sits betweennrf-ble-snifferand Wireshark.

It’s typical end-user interaction patterns are therefore via:

- The Wireshark GUI. The extcap plugin installation process is now a case of simply executing

nrfutil ble-sniffer bootstrap. - The CLI of the

nrfutil ble-sniffer sniffcommand. This currently allows output to a PCAP file, and has some limited debug JSON output we address later.

The notable omission of Wireshark CLI tooling like tshark is because it no longer “just works” and that tackling that problem is a primary focus of this post.

Other tasks you might expect an end user of my scripts to need to do, like preparing the firmware of their device, are now accomplished with other installable subcommands within nrfutil, e.g. the device package.

Requirements for my use case#

Before we deep dive into the challenges and solutions, let’s clear up what I need.

The goals likely align with those of many others. I need to be able to build automations/scripts that:

- Can ingest BLE packet data from nRF Sniffer devices.

- Can feasibly deserialize that BLE packet data into common formats for further processing.

- Are able to “tail” incoming BLE packets indefinitely in real-time.

- Are able to filter on protocol specific packets.

- Are based on mechanisms feasible to achieve on both Windows and Unix.

- Work in a simple shell environment. Such that:

- They do not have a dependency on a GUI.

- Are easily composable.

- Are simple to use:

- For those unfamiliar with this area.

- For those who may be interfacing with an nRF exclusively through the script in question to achieve it’s specific goal.

Deciding the target nRF software#

Let’s get one thing out of the way. You can already achieve the live-tail BLE packet capture aspect with tshark and the old Python extcap plugin out of the box and it’s what you’d expect: things like tshark -i <interface> -l just work, at least on the version I used. I note that there are historic complaints about this not working with this version either, but I wasn’t able to reproduce that.

So, that’s it then? Not for me, but it might be for you. You should consider if the old ecosystem is good enough for your use case. There are many cases, like a one-time ad-hoc scripting use case where it almost certainly is fine.

I wanted to target the new nrfutil ble-sniffer tooling for my use case because there are some considerations that are relevant:

- The wider ecosystem that enables flashing the device and installing the extcap plugin are actually things I’d like to orchestrate as part of the wider story of my scripts, so that is compelling. Especially since I want to do that cross platform, which could be otherwise particularly tiresome to have to implement in userland in the case of device firmware flashing.

- Since I wan’t something portable and long-lived, it seems perhaps unwise to base it on the older platform. But I expect many would contest me on that.

- Admittedly, yes, I also just like the idea of solving it out of pure curiosity, with the potential to help the many others who’ve previously asked about this.

As mentioned in my breakdown, the new ecosystem is closed source. However, whether it is open source or not simply doesn’t currently factor in my requirements list on a fundamental level, and so this isn’t really a salient factor in my case.

It is a salient factor that it is new though, if basing this choice on my own time and effort. That leads to challenges around feature gaps and documentation. However, this post hopefully removes or reduces this factor out of your own decision by way of providing solutions to those challenges.

Getting the stream packets#

To do anything meaningful, any surrounding script or tool that wants to process data in real time needs the basics:

- It will orchestrate commanding the device to start capturing traffic and ultimately route the raw byte stream such that is accessible to you in real-time.

- Have a means to be able to access the data contained therein in an idiomatic way in your language of choice. That means at some point the raw byte stream is decoded into some localised representative structure that is essentially a stream of clearly delimited and consistently structured packets, such that you can directly address all elements of the packet structure as defined in the BLE spec.

The first point is clearly something we will hand off to the nRF tooling which itself will hand off to some lower level device drivers at some point.

You would of course have to have a particular wish to reinvent the wheel from scratch to go and implement the second point yourself. A typical route would be to lean on Wireshark. It is therefore predictable and expected that when it comes to the actual meaningful user interaction with the packets, the nRF tooling provides shims that make it Wireshark’s task. In the context of scripting, that would be tshark, which is part of Wireshark, but more on that shortly.

Of course there are other less generic and more scoped options in the Bluetooth space. Libs like BlueZ are particularly ubiquitous in BLE software stacks, and I will need another post to outline how I am also using it as a part of a specialised MITM BLE proxy that serves as alternative approach to my goal in this one (over the air key extraction of an IoT device).

I am stating the obvious, to outline the resultant frustration that at the moment, there’s no apparent first-class documented way (as in, “here is the Unix shell route to pipe a to b”) to achieve this with nrfutil ble-sniffer sniff whilst staying within my requirements, without compromising on something. Well, that is, until I figured it out anyway and made this post. But it would be better if it were much more obvious in the first place.

Problem 1: tshark -i capture doesn’t stay open with extcap plugin#

Wireshark with the extcap plugin does what I want in that it is a live view of incoming packets. It works great in the Wireshark GUI, but I need this experience in a shell environment outside of the GUI in order to process the packets as they arrive in way I can programmatically process them. Completed PCAP dump files are not an answer since that wouldn’t be real time.

tshark is the CLI interface of Wireshark, so the most direct approach is to use that configured to connect to the same interface as the one configured by the plugin, which is already visible & working in the Wireshark GUI. This would be convenient since when starting a capture from Wireshark, the extcap plugin binary nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shim automatically starts the nrfutil-ble-sniffer core binary

Unfortunately just firing off tshark with the latest version of the extcap plugin (at the time of writing) installed by nrfutil ble-sniffer bootstrap does not work out of the box:

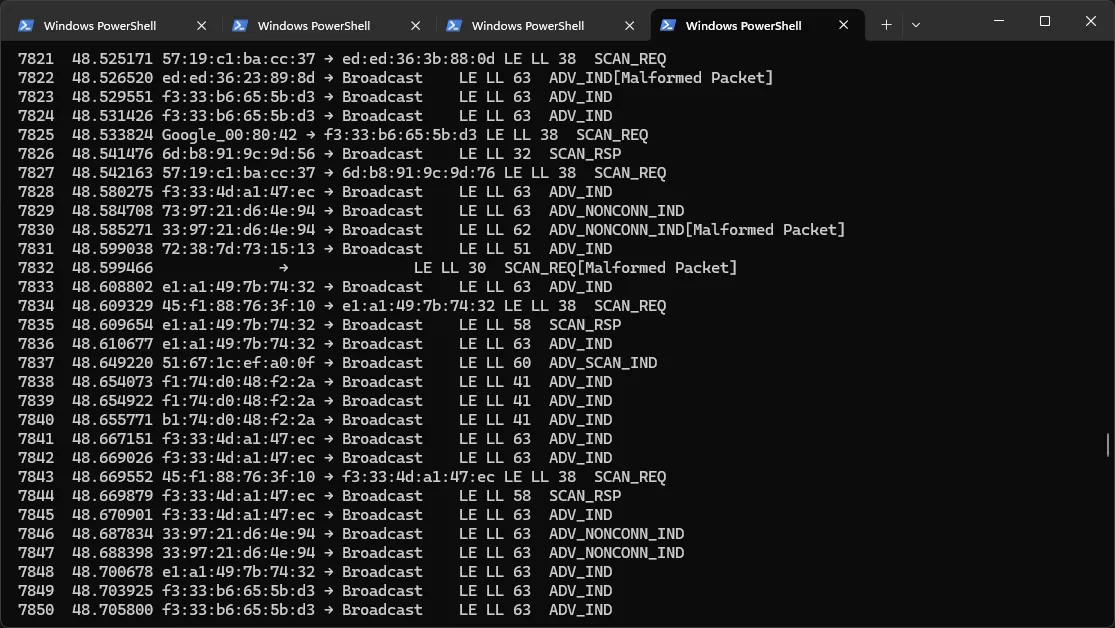

Capturing on 'nRF Sniffer for Bluetooth LE COM6' 1 0.000000 xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx → Broadcast LE LL 63 ADV_NONCONN_IND 2 0.000563 xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx → Broadcast LE LL 63 ADV_NONCONN_IND 3 0.009282 xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx → Broadcast LE LL 63 ADV_IND 4 0.010509 xx:xx:xx:xx:xx:xx → Broadcast LE LL 60 ADV_SCAN_IND4 packets capturedThe capture abruptly ends with no error state very briefly after it starts capturing. No amount of deep exploration of tshark flags was able to resolve this issue. Under debug, tshark just reports that packet capture is being stopped.

At least we can see it is capable of parsing and displaying the few packets that are captured in the short windows it stays alive.

Problem 2: nrfutil ble-sniffer sniff doesn’t make piping capture data easy#

We know nrfutil ble-sniffer sniff stays open and doesn’t end early. So can we just pipe its output to tshark -r - to ingest the data over stdin? Well, actually you can achieve this, but only after some deeper exploration I’ll save for the next section.

It isn’t as clear and obvious as you might hope, and the challenges vary in size according to the platform you are targetting and the compromises you are willing to make. At the core of the problem is that the only way to access the data itself is via a file reference passed to the command as --output-pcap-file <path>.

Trying to use the stdout#

I tried to configure the ble-sniffer sniff flags to output to stdout. There are some promising flags available that look like they might give us what we want. For example:

nrfutil --log-output=stdout --log-level=debug --json ble-sniffer sniff --port <com-port>This outputs some JSON formatted debug entries which consist of:

- Objects containing meta information about the tools version.

- Objects signalling that a new device has been found.

- Objects about operations internal to the tool.

- And finally, and somewhat promisingly, some indication of a packets contents.

Sadly the actual capture bytestream is not among this data. That continues being written into a file. However, it may seem interesting though that there is some data about the packet contents in the log output regardless, but that packet data is not oven-ready to consume:

{"type":"log","data":{"level":"DEBUG","message":"Parsed packet: Packet { header: Header { id: PacketId(2), packet_counter: 14860, protocol_version: VersionX(3), payload_length: PayloadLength(Right(53)) }, payload: EventAdvertising(EventAdvertisingPacket { header: Header { flags: AdvertisingFlags { crc: 0, aux: 0, resolved: 0, phy: 0 }, inner: InnerHeader { metadata_length: 10, channel_index: 37, rssi_sample: -70, event_counter: 0, fw_timestamp: 2159642126 } }, payload: BleRadioPacket { metadata: UncodedPhy(UncodedPhyMetadata { access_address: [214, 190, 137, 142], header: Adv(AdvPhyChPduHeader { adv_type: ADV_TYPE_ADV_SCAN_IND, tx_addr_type: Random, rx_addr_type: None, length: 34 }), padding: 0 }), data: Unknown([131, 77, 33, 200, 35, 118, 3, 3, 159, 254, 23, 22, 159, 254, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 12, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 240, 192, 145, 82, 63]), crc: [0, 0, 0] } }) }","timestamp":"2024-12-09T21:00:16.854Z"}}It is clear that this is some serialised debug output of a structure within the tool, but that serialisation doesn’t result in valid JSON. It could probably be parsed, but hooking into what is evidently debug structures in this way wouldn’t be robust. Besides, I really want to get tshark working, and that requires the PCAP stream. Parsing this non-standard format doesn’t really get you anywhere meaningul with regards to that aim.

Out of curiosity, I did use an AI model to have a go at taking in an example structure in attempt to identify what libs it originates from, and it accurately inferred that this was probably a reflection of some BLE bindings for Rust shoved through std::fmt::Debug. This is semi-important as it implies there is some packet processing happening within nrfutil itself, which makes sense given that the debug log output recognises new devices. That means it is doing more than just a straight dump of the bitstream into a PCAP. This could purely be for the logging or something more, which we will come back to.

Just read from the file?#

One solution is to simply script this in such a way as to have the ble-sniffer sniff command outputting to a file and running concurrently with a job to tail that file and feed the data into tshark -l -r -.

This works but, fundamentally, writing a file to disk which is forever growing means that this would have storage constraints that whilst small, are annoying to manage if you want this to be able to run indefinitely. You could probably actively trim that file in your own script, but its not trivial to do that in a way that doesn’t corrupt it since it is a binary format. It also means tshark is not the thing writing the capture if you do want to write something to disk, and that’s irritating because it means you can’t meaningfully use the built in log rotation functionality via its -a flag.

Those who are well-versed in Unix will be screaming at me that I don’t have to write the file to disk at all. That is part of the upcoming solution. However, Windows is not so clear cut and I care about that target in my case.

Arriving at the solution#

We need to somehow get ble-sniffer sniff to write its output to an ethereal stream appropriate for the target OS. That stream should be FIFO, such that the listener processes the dat as it comes. It should all happen in memory ideally.

What I just described is just a “pipe”, which all OSs have. But how they are able to manifest in each OS matters for this particular problem.

Since the tool needs to be passed some “file” specifier to --output-pcap-file <file>, we specifically need a Named Pipe such that the pipe is addressable by some identifier. Essentially, we wan’t to ask ble-sniffer sniff to write to this pipe, where we can then capture it and pass it to tshark -l -r -.

Windows#

On Windows, Named Pipes don’t manifest as “file” that acts as a pointer to that pipe. Instead they have they are addressable by a different naming scheme, e.g. \\.\pipe\BleCapture.

There are APIs/libs to create a Windows named pipe in any general purpose language. Here we will use Powershell, in keeping with my aim to get this working in simple native shell environment.

There doesn’t appear to be any low-level binaries built into Windows to interact with named pipes from the old-fashioned cmd.exe, but I did have success with windows-named-pipe-utils. However I want what I’m doing in this post to be in clear view and not hidden behind compiled binaries, hence I’m opting for PowerShell.

Failed Attempt: Using a pipe with --output-pcap-file directly#

Lets create a debug script to create and read from a named pipe:

# Create the pipe$pipe = [System.IO.Pipes.NamedPipeServerStream]::new( "BleCapture", [System.IO.Pipes.PipeDirection]::In)Write-Host "Waiting for the writer (tool) to connect..."

# Wait for connection$pipe.WaitForConnection()Write-Host "Pipe connected."

try { $reader = New-Object System.IO.BinaryReader($pipe) while ($true) { $buffer = $reader.ReadBytes(1024) if ($buffer.Length -ne 0) { # Do whatever with the buffer. Here we meaninglessly # print a base64 of it to the console. $base64Data = [Convert]::ToBase64String($buffer) Write-Host $base64Data } }} finally { $pipe.Close() $reader.Close()}This snippet is simplified, but here we are creating a pipe in the In direction (since we are ingesting data from it) and then pulling data from it. For the sake of example we just dump the output into the console, but theoretically you can send that data on to anywhere, including tshark. It should be addressable as \\.\pipe\BleCapture.

As I feared, unfortunately just passing this reference to --output-pcap-file doesn’t yield success:

nrfutil ble-sniffer sniff --port <com-port> --output-pcap-file "\\.\pipe\BleCapture"

Error: Failed to create capturer

Caused by: 0: Could not create capture file \\.\pipe\BleCapture 1: The parameter is incorrect. (os error 87)However, my basic debug script does register a connection to the pipe very briefly by logging Waiting for client...Connected. But the nrfutil process errors out before actually writing anything to it. Unfortunately, pipes are not real files, and some software using certain Windows API’s (particularly around file creation) won’t “just work” with pipes since their assumptions about files are baked in. And sadly, there is no true way to make pipe act exactly like a file, including trying to create symlinks from a file to a pipe.

Finding an alternative path#

Things would certainly be easier if named pipes worked natively with --output-pcap-file, and we can cross our fingers and hope that will arrive. But not wanting to be deterred, and equipped with the knowledge that the Wireshark GUI is doing this somehow, I started to analyse how that case is functioning.

We can fire up Wireshark and kick off a capture in the GUI, which will internally use the extcap plugin that I previously installed with nrfutil ble-sniffer bootstrap. By using the venerable Sysinternals Process Explorer I can then observe how the various executables are chained, with the goal being to figure out the IPC mechanism that makes it tick.

Here’s the condensed process tree, including the arguments being passed to each (in my specific instance, so there are references to the COM port the sniffer is connected to on my machine):

Wireshark.exe└── nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shim.exe --capture --extcap-interface COM6-4.4 --fifo \\.\pipe\wireshark_extcap_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-out \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ext_to_ws_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-in \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ws_to_ext_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --scan-follow-rsp --scan-follow-aux └── nrfutil.exe ble-sniffer --capture --extcap-interface COM6-4.4 --fifo \\.\pipe\wireshark_extcap_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-out \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ext_to_ws_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-in \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ws_to_ext_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --scan-follow-rsp --scan-follow-aux └── nrfutil-ble-sniffer.exe --capture --extcap-interface COM6-4.4 --fifo \\.\pipe\wireshark_extcap_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-out \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ext_to_ws_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --extcap-control-in \\.\pipe\wireshark_control_ws_to_ext_COM6-4.4_20241214180029 --scan-follow-rsp --scan-follow-auxThere’s a few things to take in here:

- As expected, the extcap plugin binary

nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shimspawnsnrfutilas a child process which is performing the actual capturing.nrfutildoes that via another child processnrfutil-ble-snifferwhich is a binary that is installed when theble-sniffercommand is installed by the user. - There is an undocumented CLI API on

nrfutil ble-snifferthat appears to be based around--capture. - That undocumented CLI API also uses flags to indicate named pipes, which is promising!

--fifois most likely the pipe used for the capture bytestream.- The

--extcap-control-inand--extcap-control-outappear to be control channels for the Wireshark GUI and the extcap plugin & associated process chain to communicate in order to provide UI controls to configure the capture without restarting it. The only (loose) documentation I could find for that is here.

- Other flags like

--scan-follow-rspand--scan-follow-auxare documented vianrfutil ble-sniffer sniff --help. These appear to be the same and just passed through.

So now we know there is indeed a CLI interface that evidently works with Windows named pipes, I was able to focus on getting this mechanism working with the pipes being created and handled by my script instead of the Wireshark GUI. After some methodical exploration by way of using this new information to call these binaries manually, I was also able to determine:

-

Calling

nrfutil.exe ble-sniffer --capture --extcap-interface <com-port> <other-flags...>directly and in any configuration claims--captureis not an available flag. I suspect this is only available when launched as a child process to the extcap shim. -

Calling

nrfutil-ble-sniffer.exe --capture --extcap-interface <com-port> <other-flags...>directly and in any configuration, immediately exits. Again, I suspect it can only be launched as a child process tonrfutil. -

Calling

nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shim.exe --capture --extcap-interface <com-port>(inside the Wireshark extcap plugin directory):- With only the

--fifopipe defined, it sends data very briefly before stopping. This the likely underlying cause oftshark -i <interface>doing the same as I described earlier.nrfutilexpects the Wireshark GUI-specific control pipes to be available. - With

--fifoand the--extcap-control-incontrol channel pipe it works, even if you only create thePipeDirection::Outpipe and don’t make any attempt to push control data down this channel in the way Wireshark GUI does. - The

--extcap-control-outdoes not seem to be required. This is the channel the shim otherwise uses to talk back to the Wireshark GUI.

- With only the

-

Calling

nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shim.exe --extcap-interfaces --extcap-version 1.0:- Allows you to list relevant nRF sniffers, including their COM port string.

- From this I was able to determine that the part of the COM port identifier after the hyphen as passed to

--extcap-interface, e.g.4.4inCOM6-4.4, is actually determined by--extcap-versionwhich seems to align with the<major>.<minor>of my current Wireshark version. - We are unlikely to care about this version string in the first instance, if we don’t intend to implement the handling of the control channels, so we are likely safe using any sane value.

Basic POC solution#

Armed with this information, I can finally converge on a solution. This snippet contains the fundamentals and acts as my proof of concept of the approach. There is more to be done, which we will get onto.

$jobs = @()

$cancellationTokenSource = New-Object System.Threading.CancellationTokenSource$cancellationToken = $cancellationTokenSource.Token

$fifoPipoName = "BleCaptureFifo"$fifoPipe = New-Object System.IO.Pipes.NamedPipeServerStream( $fifoPipoName, [System.IO.Pipes.PipeDirection]::In, 99, [System.IO.Pipes.PipeTransmissionMode]::Message, [System.IO.Pipes.PipeOptions]::None, 65536, 65536)

$controlInPipeName = "BleCaptureControlIn"$controlInPipe = [System.IO.Pipes.NamedPipeServerStream]::new( $controlInPipeName, [System.IO.Pipes.PipeDirection]::Out, 99)

$jobs += Start-ThreadJob -ErrorAction Stop -Name $fifoPipoName -ScriptBlock { $pipe = $using:fifoPipe $token = $using:cancellationToken

$asyncTask = $pipe.WaitForConnectionAsync($token) $asyncTask.Wait()

try { $reader = New-Object System.IO.BinaryReader($pipe) $bufferSize = 4096 $buffer = New-Object Byte[] $bufferSize

while ($true) { $memStream = New-Object System.IO.MemoryStream

do { $bytesRead = $pipe.Read($buffer, 0, $buffer.Length) if ($bytesRead -le 0) { break } $memStream.Write($buffer, 0, $bytesRead) } while (-not $pipe.IsMessageComplete)

if ($memStream.Length -eq 0) { continue }

$data = $memStream.ToArray() Write-Output $data } } finally { $reader.Close() $pipe.Close() }}

try { while ($true) { $jobs | Where-Object { ($_.HasMoreData) -or ($_.Error) } | Receive-Job -ErrorAction Stop }

} finally { $cancellationTokenSource.Cancel() $fifoPipe.Close() $controlInPipe.Close() Stop-Job $jobs Remove-Job $jobs}To run this very raw and simple example you must first run the script in at least PowerShell 7 (Windows currently ships with PowerShell 5.x) and pipe it into tshark. E.g.

.\blereader.ps1 | & 'C:\Program Files\Wireshark\tshark.exe' -l -r -Secondly, execute the extcap plugin binary to connect to the pipes used by this script, e.g:

. "$env:APPDATA\Wireshark\extcap\nrfutil-ble-sniffer-shim.exe" --capture --extcap-interface COM6-4.4 --fifo \\.\pipe\BleCaptureFifo --extcap-control-in \\.\pipe\BleCaptureControlIn --scan-follow-rsp --scan-follow-auxAnd finally, we have live-tail parsing of the BLE packets via tshark in Windows:

Taking this further#

I am working on a PowerShell module which I will publish on GitHub soon (and update this post) to make this more prod-ready:

- Auto detection of

nrfutilandtsharkpaths for easy execution. - Automatically parallelise and configure the

nrfutil ble-sniffer sniffjob with thetsharkjob. - Detect if the required

deviceandble-sniffersubcommands have been installed intonrfutiland automatically adds them if not. - Automatically finds the port of the sniffer device so it doesn’t have to be manually provided.

- Warn if other sniffing processes are running, which can prevent data from being received.

- Automatically terminate the sniffer process if the script dies.

- Add options to outputs PS objects for packets as represented by tshark which means your can pipe the script to PS tools like

Out-GridView,Format-List,Format-Table, etc. for PS-native formatting.

Unix (including Mac OS)#

The Unix flavour of nrfutil is relatively easy to deal with. We do not need to use any undocumented interfaces or semi-internal binaries like I described for the Windows approach. That’s primarily because named pipes in unix-like environments already manifest as “files”, and that is what --output-pcap-file accepts.

First we simply call mkfifo to create such a named FIFO pipe (should be available on any distro and Mac OS). Then we run nrfutil, with --output-pcap-file pointing to that pipe. E.g.

mfifo ./capturenrfutil ble-sniffer sniff --port /dev/ttyACM0 --output-pcap-file ./captureNow in a different terminal session or as a background job we can read from this pipe and pass it to tshark:

cat ./capture | tshark -l -r -And that’s it!

Further work#

I would like to explore dynamically changing BLE sniffer settings on the fly (e.g. followed device) without restarting the capture. This should be possible by using the control pipes on the internal extcap interface thhat I began exploring in the Windows section.

I also plan to formalise the more complex Windows solution into a PowerShell Module.